1945 Chengdu, China

Weiming Zhang

1937

Chengdu, China

Interviewed on February 14, 2021

by Melissa Lu

(Interview translated from Chinese)

It was the first weekend of the summer, and the sun was blistering already. As a reward for our hard-fought efforts conquering multiplication tables for the year, Mother dropped my big sister, Ling, and I off at our aunt’s house. I was around eight at this time, and Ling twelve. Now going to your aunt’s house might sound pretty lame, but let me tell you, Auntie Lan was something else. Auntie Lan was Mother’s baby sister and practically not an adult. Auntie Lan constantly wore animal print, and she loved to do anything Mother didn’t. All of our suppressed desires were fulfilled at Auntie Lan’s.

Auntie Lan was waiting outside when we got to her house. She hugged Mother and quickly sent her back on her way. I’m not sure if Ling and I even got to say goodbye to Mother. Auntie Lan took hold of us, a wide smirk spread across her face. Ling and I looked at each other. What was Auntie Lan plotting this time? She dug into her shirt pocket and waved three red tickets in our faces. “Come on, munchkins. We’re seeing a movie!”

Ling and I shrieked with delight—although truth be told, we had no idea what we were shrieking about. We were simply marveling at the potential of this new adventure with Auntie Lan. We had never been to a movie theater in our entire lives! There were none in our town.

We walked to the theater along a dirt road under the sweltering summer sun. By the time we finally got there, I was starting to feel faint. But then we entered the theater, and I will never forget the crisp, cool air that greeted us at the door. It was as if there existed two different worlds across those doors. Ah, the world of air conditioning!

The name of the theater escapes me, but I imagine it was something simple like Chengdu Theater. I was just a kid, so I didn’t pay much attention to those kinds of details. The theater was quite plain by today’s standard. There was no ticket booth, just a man at a table with a roll of tickets and an open cash box. The concession stand is what I remember most clearly. After all, they were selling my favorite peanut candies. The candies were essentially peanuts encased in a hard sugar shell and then drizzled over with a clear sweet syrup. They were a real treat, much better than the popcorn and American candies they sell nowadays. I really wanted some, but I knew better than to ask. At the time, we had no money. Everyone was poor from the war.

They sold cigarettes by the stick. A whole pack would’ve been way too profligate even for the richest man of our town. The rich men would smoke a cigarette while they watched the movie. The really rich men would buy two cigarettes, smoke one during the movie, and hang the other on their ear. It was classic, primal display of class and wealth.

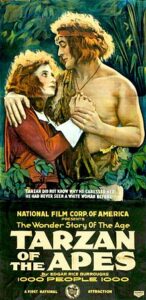

The entrance to the showroom was straight ahead. We made no detours and continued onward with empty hands. Across those doors, we upgraded yet once more. It was a grandiose room with high ceilings. Fine red curtains cascaded down from the ceiling unveiling this large white flap of a screen at the front. It was hard to imagine then that this screen would unveil so many wonders. We must’ve walked past hundreds of seats before we found our own in the front. You bought tickets for particular seats at that time, and sitting in the front or the back was always cheaper. The movie was a Western called Tarzan.

I don’t remember much about the plot, but I remember the red light. Tarzan was black-and-white by all standards, but somehow, it came off more like shades of red on the screen. I remember asking Auntie Lan, “Where is the red light coming from? Is it fire?” She laughed at me and told me to just watch the movie, but I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I would steal glances behind me, trying to find the source of the projection. Maybe there was a fire burning back there, I thought. Auntie Lan would clamp me back down into my seat though, and I never made it to the projection booth to uncover the truth.

As you can imagine, having spent most of my time looking in the other direction, I remember very little about the movie. It was a silent film, so it didn’t matter so much that it was western. Each shot spoke clearly to me, even though there was no sound. Tarzan was a boy around my age living in the jungle. He could swing from the trees and communicate with the apes. For the next couple weeks, Ling would pretend to be a baby ape, and I’d act as Tarzan, and we would create our own adventures with these borrowed identities.

When the movie ended, I felt this sort of childish stupefaction about the impossibility of the feat I had just witnessed. I had watched films before, but only through a small peephole on a device called the kinetoscope. Only one person could view a kinetoscope film at one time, and a live orchestra would play the music to pair. So, we found it peculiar, remarkable maybe, that something that had existed only in a hole before could now be projected onto this marvelous screen for 200 to 300 people to share and watch together simultaneously. The film could play its own music too. It completely altered the movie watching experience as you got to share the experience with others, react in real time, and enjoy the hour in a comfortable position.

Movies became a special place for me. I spent most of my childhood allowances on movie tickets. I actually took your grandmother to the movies on our first date and many after that. The movies became a place of comfort, happiness, and safety—an escape from my reality beyond its doors. The second world war took much from our family, including my father. At times, I liked the world within the theater doors much more than what was outside.