1958 Minneapolis, Minnesota

Jeffrey Rusten

Born 1950

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Interviewed on 2/7/25

By Disha Shidham

DS: What is the first movie you remember seeing?

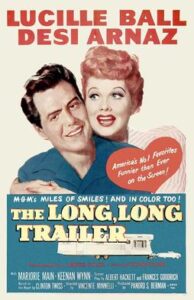

JR: Well, actually my earliest memory was from a drive-in. Almost every movie I saw was a schlocky movie. I don’t think any of them has become a classic nowadays. And, and they usually played into some, you know, a very pop culture kind of thing. So the first thing that I saw in the drive-in was a Lucy and Ricky, an I Love Lucy movie. It was in color. So that was just a shock because, you know, this would have been in the late 50s.

We watched TV all the time, but there was no color. So whenever we went to the drive-ins or the theaters, and there weren’t many in the suburbs, that’s what I remember – the color. The color seemed to distract very much from the story. But fortunately the movies we saw didn’t have much of a story.

Anyways, the movie we saw was called the Long Long Trailer. And it was Lucy and Ricky getting an enormously long house trailer and going on a trip to places like the Grand Canyon. You don’t drive into the Grand Canyon, but they were driving on roads near the Grand Canyon and almost falling off and, and she was in the back of the trailer trying to cook and being, you know, knocked all around and just one kind of slapstick scene after another.

It was good for kids and it was just that premise and that’s all I remember. I don’t think I ever really saw a movie that I had to sit down and analyze or actually had to pay close attention to as a kid.

DS: How old were you when you saw the Long Long Trailer? And where did you see it?

JR: Oh, this would have been when I was between 8 and 12 years old in the suburbs of Minneapolis.

You know, the only time we could get the TV set was on Saturday afternoon when my parents were busy and everybody else was out playing. UHF stations were just coming into being and they just played old movies. So they used to play Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. They played it about every three months, so that one really sticks out in my mind. Usually in the winter, when it was really cold and you couldn’t go outside, if Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein was on we would watch that again. It was one slapstick routine after the other. It had Bela Lugosi in it, and it had Lon Chaney Jr. playing Frankenstein. And you didn’t really know the difference because he was in makeup, he could have been Boris Karloff. And so you had this comedy duo and then. It was kind of the Marvel equivalent of that time, I guess, just bringing all these sorts of pop culture characters together.

I always liked Abbott and Costello, though I know a lot of people don’t. Many think their only real bit was the “Who’s on First?” routine, which some consider one of the weakest comedy acts ever.

One time, I decided to use that routine in class. I don’t usually bring it into lessons, but I was teaching a comedy course when I was at Cornell and when I was a junior faculty member at Harvard. It was designed to be a large class, but we ended up with about 30 or 40 students. We focused on comedy films, particularly how their plots were rooted in ancient comedic traditions.

When Trump was elected the first time, it happened to coincide with the part of the syllabus covering farce – the kind of comedy where everything goes wrong. Some comedies feature a trickster who orchestrates everything perfectly, but in farce, chaos takes over. Since it was the first day of our farce unit, I thought it would be fitting to show “Who’s on First?”

The students, however, were not on board. They wanted to talk about politics, and those who already knew the routine weren’t interested in watching it. Before playing it, I asked them why they thought it wouldn’t work – why they found it unfunny or outdated. I took a chance with it anyway.

And, to my surprise, they all laughed. They had forgotten what makes the routine funny: the growing frustration of one character. The angrier he got, the funnier it became to them.

It didn’t help with Trump, but at least it gave them something else to think about for a little while.

DS: Did you ever go to movie theaters when you were younger?

JR: Yes, believe it or not, I can only remember doing it once. There was a place called the St. Louis Park Theater, but it was quite a ways away. I went there one afternoon – by myself, I think. I’m not sure why.

My parents weren’t really moviegoers, or if they were, they must have gone without me. I still remember the movie – it was Knights of the Round Table, a King Arthur-style costume drama. What stuck with me most was the color. The costumes were all bright, pastel shades, which was unusual. But the actors were all American – no British accents. The plot seemed almost nonexistent; it was really just about the spectacle. I only saw it because that’s what was playing at the time.

I probably sound deprived, but years later, when I was in college at the University of Minnesota, my movie-going experience changed completely. My wife reminded me to talk about this: The university was in a part of Minneapolis called Dinkytown, which was like a student neighborhood – kind of like a college town here in Ithaca, but not just bars and restaurants. They had movie theaters there, and also this unique thing called the Xanadu Film Festival.

The festival was held in the basement of a Jewish fraternity. Years later, I mentioned it to David Feldshuh, a film director and professor here at Cornell, and he told me he had actually been the janitor at that fraternity at the time. And as the janitor, he got to see all the movies. The festival specialized in German films, particularly World War II movies from both perspectives. They screened things like Triumph of the Will and Olympia – Leni Riefenstahl’s work, which was shocking to watch.

But they also showed the other side of things, like To Be or Not to Be, starring Jack Benny. That was an incredible movie. I think it was directed by Lubitsch, but I’m not sure. It was from the late ’30s, and Benny played a Polish actor who performed Hamlet regularly. He ends up trying to escape from the Nazis while pretending to be one. It was a comedy – really astonishing.

What stuck with me most wasn’t just the German films, but the 1930s films in general. From that point on, I tried to watch as many American films from the ’30s as I could. When I later taught my comedy course, I focused on those films, studying them in depth, along with some from the early ’40s.

At the same time, I had a job at the university indexing the Minneapolis newspaper. I was assigned to index the year 1942, and I was probably the slowest indexer they ever had – I read the paper cover to cover instead of just skimming for keywords. It was really fascinating.

My job was to man the desk in the evening at the newspaper room, which didn’t require much. So I would sit there reading these huge bound newspapers, especially the movie reviews, and correlating them with historical events. That was incredible. In fact, 1942 was the year Casablanca came out – coincidentally, that was also when Roosevelt and Churchill held a secret meeting in Casablanca.

Yeah, it was all over the front page. It was a huge shock – imagine, in the middle of the war, Roosevelt and Churchill actually meeting in North Africa. One of them had flown across the Atlantic, and they were there, in the middle of it all. It was incredibly daring.

And then Casablanca premiered at the same time, though the movie had nothing to do with the meeting.

There was also Sands of Iwo Jima, which covered more recent history – but not very accurately, I’m sure. That got me interested in movies from that period, too.

DS: Do you think you were drawn to World War II-era films to better understand the social consciousness of that time?

JR: Yeah, I guess so. I wasn’t really a history buff, but that era felt very alien to me. I could look things up and understand them intellectually, but it still seemed distant. Oddly enough, I never asked my father about it. He was actually in North Africa during the war – not as a combat soldier, but as a photographer. Now that I think about it, I never asked him about the movies from that time either. He probably never saw them since he wasn’t in the U.S. then.

When I got into comedies, I discovered that the ’30s and ’40s were a golden age for really well-plotted and well-written comedies. When I taught my comedy course, I made sure to set up each film carefully. Instead of just asking students, “What did you think?” I gave them specific questions and key quotes to focus on.

There are two films in particular that always amazed my students: Bringing Up Baby and The Lady Eve by Preston Sturges.

You know, The Lady Eve is a fascinating film. If you just stumbled upon it on TV, you might think it’s cheesy – the dialogue is so mannered, the characters are over the top, and it feels like it’s all happening in a nightclub with music constantly playing. But if you really pay attention, you realize it’s incredibly structured.

I always tell my students: You’re going to think the movie is over 40 minutes in – but it’s not. That’s just the setup. Everything in the first 40 minutes tells a complete story, but it’s really laying the groundwork for a problem that seems impossible to solve. Barbara Stanwyck’s character has a plan, and no one – including the audience – knows what it is until the very end. And when you finally see it unfold, it’s brilliant.

And Bringing Up Baby is another one that always got a huge reaction from students. Before streaming, I used to put movies on reserve in the library, where students could watch them with headphones in these little cubicles. I was eventually told to stop doing that – because students watching Bringing Up Baby would laugh so loudly they were disrupting the entire library!

The Lady Eve is beautifully scripted and carefully acted, whereas Bringing Up Baby – while structured – is largely improvised in terms of dialogue. Yet both films share similar characters: a clever, strong-willed woman manipulating a handsome but clueless man. In one, it’s Barbara Stanwyck; in the other, Katharine Hepburn. The male leads – Henry Fonda in The Lady Eve and Cary Grant in Bringing Up Baby – are both playing against type as good-looking but completely clueless men. In both films, the women are trying to seduce them – and, in a way, take their money – but in a surprisingly affectionate manner.

And that dynamic isn’t obvious at first. The films just feel like fun, chaotic romps, but if you study them, you see the careful structure behind them. In The Lady Eve, for example, I ask students to analyze a scene where Stanwyck’s character, a card sharp, needs to meet a wealthy man on a cruise ship. Every woman on board wants to get his attention, but she figures out a way to make sure she’s the only one he notices. I have students break down how the scene is staged, how the narration guides us through it – it helps them appreciate the film more deeply. Some people say you shouldn’t guide students too much before watching, but I find it valuable.

The films I chose weren’t just personal favorites – they were meant to illustrate different types of comedy. I structured the course non-chronologically, focusing on distinct comedic plot types. One of the main ones was the trickster comedy, where a highly intelligent character manipulates everyone in unexpected ways. The Lady Eve is a perfect example because its protagonist is incredibly sharp and always one step ahead. Then there’s farce, which is the complete opposite – where everything goes wrong due to misunderstandings and absurd situations. Those were the two core comedic structures I focused on.