1965 Pretoria, South Africa

‘The Movies’ in 1960s South Africa

Juliet Calcott, Born 25 December 1954

Pretoria, South Africa

Interviewed Wednesday 5 February 2025

By Lucy Calcott

My mother was born during a period of crisis. The Nationalist Party shocked the world by narrowly winning the 1948 election, instituting the system of Apartheid. For liberal South Africans, this was a massive shock – the nazi’s had lost in Europe, but here in our own country, their ideology had won. The Apartheid movement was deeply anti-British and pro-Afrikaner, backed by the secret-society Afrikaner ‘Broeder-Bond’ (‘band of brothers’) which aimed at protecting the remains of the Afrikaner community that had survived the 1899-1902 South African war. Over a third of all Afrikaners had died in British concentration camps during the war, and the legacy of that pain drove a wedge into the heart of society. Everything from the packaging of the bread they ate to the kinds of car they drove would be defined after that by the system of Apartheid. My grandparents tried to protect my mother, the only English-speaking white girl for miles around, from the realities of what was going on, hiding their political affiliations from their neighbors to keep her safe. In 1965, when she was ten, my grandmother took her for the first time to the nearest city, the ‘bright lights’ of Pretoria, for her first real taste of the world.

What is the first movie you remember seeing?

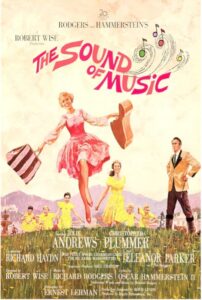

The first movie I remember seeing was the Sound of Music, which I saw in Pretoria. It was massively exciting. They had changed the name to make it in Afrikaans – it was called ‘Die Geluid van Musiek’.

The theatre had a single screen but seating on both sides – they projected the film onto that big screen (which was almost like a sheet). If you sat on the ‘white’ side of the screen, you watched the movie right-way-round. If you sat on the other side of the screen, in the ‘black’ section, you watched it backwards. We couldn’t see them, and they couldn’t see us, but when there was a joke, we could hear each other laughing.

What do you remember about the movie?

It was just magical. I didn’t see it again until I had my children in 1996, 1997 and 1999 – I had you all pretty late, too, so it was a long time. The memory was alive for me throughout all those years. I think the music is what made it so vivid. It was the first, and one of the only experiences I had of going to watch a film in a theater until I finished university. We lived in such an isolated place we didn’t go to watch films, and it was very difficult at the time to get to the city. It was also dangerous, and my parents didn’t want me to be living in that world, there was so much that was normalized about it which they couldn’t accept, and they didn’t want to put a little child in the position to have to lie.

The school near us got a projector around when I must have been in high school. We’d go to the hall and watch films – it was very limited what we could watch, though – only Tarzan and Jane movies and cowboy movies. We understood cowboys, out in the North. People went most places by horse, and that was true really until I graduated highschool. The roads were also so bad, and sometimes so steep, they were impassable in the motorcars. But we didn’t understand about the ‘Indians’ – we thought they were maybe a bit like legends, or like when people talked about elfs or unicorns.

The audience was always all-white, mainly Afrikaans people. People sometimes hired that projector to watch films in people’s homes. I remember for my cousin Jilly’s birthday they hired it to watch ‘Lassie’, I got so stressed that I held onto her finger so tight I nearly broke it. It felt so real, and I wasn’t used to that feeling that you were watching a story right in front of you that wasn’t a true story.

We didn’t have television of course until 1975 – the nationalist party government thought that if we had television, dangerous ideas from the West would come into the country. They were controlling the narrative, and it was cut-throat. Nothing got through. Even in the 1980s you could buy a Readers Digest and Time Magazine with blank pages – those blank pages were the article on South Africa. In the newspapers, if something had happened, they weren’t allowed to print it, so they’d print a black block to indicate to people that something had happened. Then the government changed the rules again and said they weren’t even allowed to print black blocks. Then they would just leave a blank space – so you knew something had happened, but you didn’t know what it was.

Of course, television and films were even more dangerous – far too dangerous. They didn’t allow it at all until 1975 – and then it was only one channel, and it alternated English and Afrikaans. We called it ‘the television’ – because that channel was the only thing we had – and it was completely controlled by the government. That was 1975. But by the 1980s, there were channels in lots of different languages, and it wasn’t like that anymore, but it was still incredibly tightly censored.

What did you think of the character(s), actor(s), story?

It’s so difficult to say what I knew then – because I know it so well now – but I know that I was totally struck by the beautiful mountains, the man who played the guitar, the woman with the apron who sang to the hills.

The NATs (the nationalist party, the party of Apartheid) weren’t overtly pro-nazi, we had our own unique racism, but they were definitely not anti-nazi, so in the translation they changed some of the words to not be so anti-nazi. But I spoke English, so I could see when they’d changed the words because the dubbing stopped matching.

They showed shorts before it – adverts for Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes. At the end of the second-world-war, South Africa was still part of the commonwealth. My ma used to say that before 1960, when South Africa pulled out of the commonwealth, there was an intense struggle between the anti-apartheid community who wanted to stay in the commonwealth, because they believed in multi-racial values, and the pro-apartheid people who hated the English and wanted to leave. So until 1960, when they finished a film, they played ‘God Save the King’. Those South Africans who were pro-Britain would stand up out of respect and in protest, and then those who were pro-Germany and pro-Apartheid would beat them up. Ma said there was a punch-up after every movie. And they knew it would happen, the ones who would stand up. It was during the war and in the 1950s – that’s how it always was. Finally the pro-Britain group lost the fight and the NATs left the commonwealth. The government didn’t want anything to do with Britain. Then they never played ‘God Save the King’ again. The commonwealth was very racially integrated, and the NATs hated that.

How did you get to the theater/venue?

We drove to the theatre – we lived out on the farm. We had an oval station-wagon. It took about three hours, and the car would be packed to the gunnels with everything we needed. The dog of course had to come as well. There were no seatbelts, so I used to lie on the back and sing and sing and sing. Or I would sit at the front with my mom and watch the cars whizzing past. The road up to the north was very narrow, it was a track, so when the cars passed each other, both vehicles would shake and veer off the road. You could feel the wind of the other vehicle passing and it rocked the car. Back then, there were no clean toilets anywhere, nothing in the North, just holes in the ground, so you made a plan on the side of the road.

Was there a concession? Did you have a favorite candy?

At the theatre they sold salty popcorn, so we loved that, and they had little bottles of coke.

Do you remember the name of the theater? Were there ushers?

I can’t remember what the name was, but I remember it was a huge occasion. I was dressed in my best clothes – my Sunday clothes. It was just before my littlest brother was born, and so I think mum was trying to comfort me because she knew as the only sister it was going to be a lot of work as soon as he was born – for both me and her. So it was our last big hoorah!

A little later there used to be a drive-in, and we would drive the car in and put the speaker into the window and watch the movie on the big screen. We went as a once and I remember how exciting that was. But they had to check every car to make sure there were no black people in the back– because if you drove in with a domestic worker, pretending to just be going into the town, and then went into the drive-in with them hiding in the back, the authorities would fine you. It wasn’t allowed for white and black people to have ‘recreation spaces’ together, so as soon as you went through the gates you had to separate.

What town and year was this?

It was in Pretoria, 1965. And I remember it was very busy. There were no shopping malls, all the department stores were separate, and you had to walk up and down the pavement. They had a veranda roof over all the pavements, and the center of Pretoria was very smart. As a child you don’t think about color, but I know that it would have been very white. It just never really occurred to me that the city wasn’t white, because I saw it so rarely, and I had nothing to compare it to. Of course, Pretoria has collapsed now, and it’s funny to think that if you were to step out of your car there today you would get shot. Like Uncle Miko. It’s a new world now – and the poverty has only got worse. All of the recreation facilities that used to be around were not able to adapt to the safety challenges. Now that you can’t drive anywhere in central Pretoria after the sun goes down, all those night-time activities never happen anymore. There are theatres on the outskirts, but the center of Pretoria is a no-mans-land now where the police are even too afraid to go. They’ve left it to the gangs – and the gangs live in those old, historic remnants of the world we used to know.

I remember those early trips to the city as a farm girl. I barely wore shoes, we barely had any, and here the women wore crimplene dresses and miniskirts. It was all very fascinating to me. They had beehive hairstyles – these straight up and down dresses, far above the knee, and hair like a balloon on their head. My mother tried it out once or twice but it was too much effort. I was very disappointed that she didn’t have a beehive, because I figured that if they were doing that in the city, it must be the right and proper thing.

Our family in Pretoria were very politically involved up until Sharpeville, and then after Sharpeville with the big sweep that they had they put certain members of my family into prison for 6 months, including my family doctor. And then all of those relatives emigrated to Australia. But dad wasn’t involved, because that was in the city. One of his relatives was very involved in the Black sash – which was housewives against apartheid. Another relative helped Albert Luthuli, the founder of the ANC, burn his passbook. He burned it in her basement, and she took a picture for him. Those pictures they would put up in public places – they tried to sneak them into places like theatres – sometimes hidden inside the tray tables. But if you got caught putting one up, that was it.