1946 Charleston, South Carolina

Dr. Gerald Rittenberg

Born 1940

Charleston, South Carolina

Interviewed on January 30th, 2024

by Robby Hill

Going to the movies was a huge deal for me in those early, elementary school years. A real big deal. For those two hours in a darkened theater, I’d get popcorn—no drink, but always popcorn—and lose myself in the stories. When I went to a movie at that age, I was totally wrapped up in what was happening on the screen. Other than the popcorn, the outside world was just that: outside. The movies were always well-attended for adults and children alike. All my friends would go to the same movies I did. We’d talk about them. We’d reenact them. It was more of a communal experience.

When we used to see movies, us kids would ask each other, “Did you cry in it?” In other words, was it a tearjerker? Take Bambi. In Bambi, the fawn grows up to be a deer and the mother dies as a result of the big forest fire. The next day you’d see your friends and ask them, “did you cry?” If you said you didn’t cry, then that made you a real tough guy. Remember, you’re seven or eight years old, so everybody cried, whether they said it or not.

I remember all the theaters, too. Downtown, there was the Gloria, the Riviera, the American, the Arcade, and the Garden. The Gloria had a large auditorium and a domed ceiling that was lit up like a skylight with stars all over. It made you think you were looking up at the night sky. To a kid at that age, it was magical. Those were the years when movie picture theaters were like real palaces.

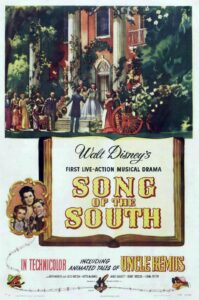

It was at the Gloria where I remember seeing my first movie, Walt Disney’s Song of the South. I was about five or six years old when that movie came out. I went to it with my parents and my sister, Carol. We all walked from our home on Gadsden Street to King Street where the theater used to be.

Song of the South was the movie adaptation of the Joel Chandler Harris Uncle Remus stories, and it was partially animated. The stories that the character Uncle Remus told a group of children were animated while most of the rest was live action. That said, the big draw for kids was the animation. It was a funny, delightful experience for a child getting to see these animated characters going through their antics and shenanigans. The Disney characters like Br’er Fox, Br’er Rabbit, and the song “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” were, to me and other kids, just upbeat and hilarious.

I also remember the narrative parts; I remember the stories so well that I could probably repeat them verbatim. The vernacular, the way the story was relayed by Uncle Remus, the characters’ patois…it embedded very quickly and early, and it stayed with me.

When I saw the movie Song of the South, I was probably no older than six. I don’t recall my parents’ reaction. At the time, all I knew was that it was a children’s movie made by Walt Disney. It wasn’t until later in my youth that I recognized the racial disparities in the film. To my knowledge, Song of the South has never been re-released in the modern era. I don’t know when it went out of distribution, but I’ve never seen it on DVD. Whereas the other Walt Disney movies from that time—Pinocchio, Cinderella, and so on—were more-or-less okay, at least in terms of not having serious racial problems, Song of the South certainly had them.

Coming from Charleston, Song of the South seemed fairly normal to me. It was of course a very segregated society, and the African American people I knew were mostly domestic workers. That’s just the way Charleston was organized then. Those were the days when every movie had uniformed ushers, and in Charleston, they were all white and all male. I don’t think any African Americans were allowed in the theaters downtown, not even in the galleries. There was a theater uptown, above Calhoun Street, called the Palace, but my parents never took me there. The Palace had a large gallery where African Americans were allowed to sit, and come to think of it, that may have been why we never went there. It never really occurred to me why, but that could have been the reason.

When I was able to, my father gave my sister and me the books by Joel Chandler Harris that the movie was based on, so I read the stories themselves. If you ever get a hold of that book, you’ll see that they are written in the vernacular. They’re even somewhat difficult to read because of all of the apostrophes and unconventional spelling. It was really by reading the book that the stories imprinted on me. There was always a soft spot in my heart for the African American characters in the book as a result of my seeing the movie. So if I think about the long-term effect of watching the film, it might be a certain appreciation for another group of individuals who I didn’t normally have so much association with, but who seemed to have values like mine.

Relationship to interviewee: grand-nephew